- Ninguna Categoria

Douglass, Fred ``Fred Douglass``-En-Sp.p65

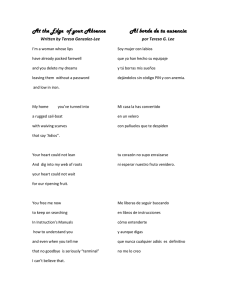

Anuncio