Cambios al sistema judicial Economista-05

Anuncio

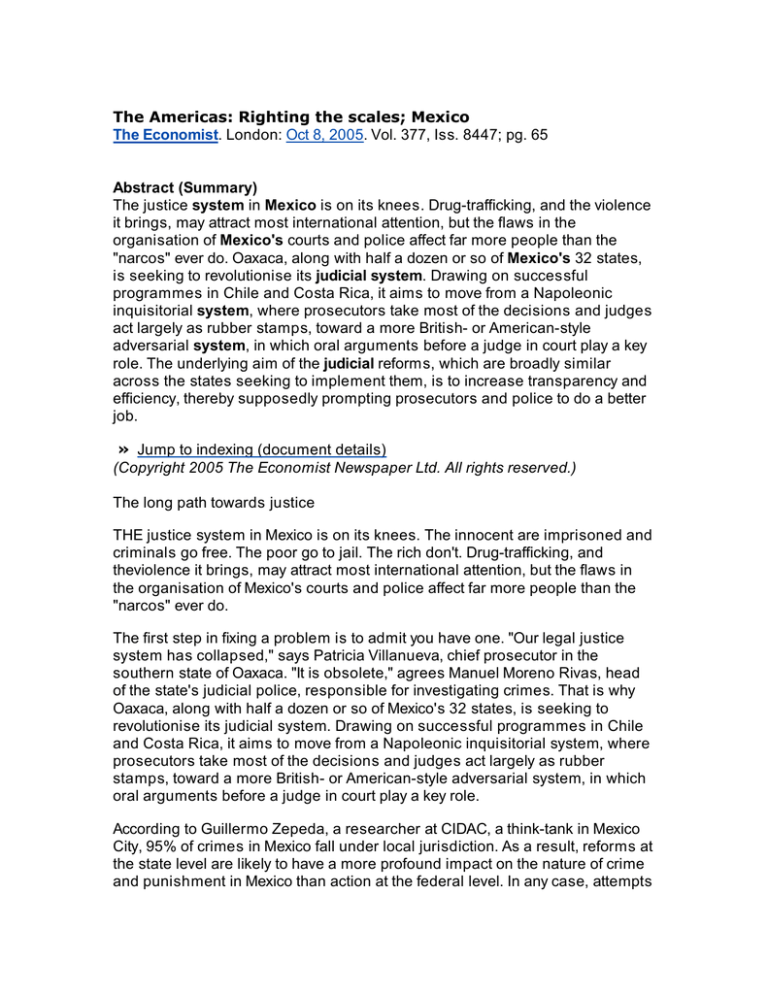

The Americas: Righting the scales; Mexico The Economist. London: Oct 8, 2005. Vol. 377, Iss. 8447; pg. 65 Abstract (Summary) The justice system in Mexico is on its knees. Drug-trafficking, and the violence it brings, may attract most international attention, but the flaws in the organisation of Mexico's courts and police affect far more people than the "narcos" ever do. Oaxaca, along with half a dozen or so of Mexico's 32 states, is seeking to revolutionise its judicial system. Drawing on successful programmes in Chile and Costa Rica, it aims to move from a Napoleonic inquisitorial system, where prosecutors take most of the decisions and judges act largely as rubber stamps, toward a more British- or American-style adversarial system, in which oral arguments before a judge in court play a key role. The underlying aim of the judicial reforms, which are broadly similar across the states seeking to implement them, is to increase transparency and efficiency, thereby supposedly prompting prosecutors and police to do a better job. » Jump to indexing (document details) (Copyright 2005 The Economist Newspaper Ltd. All rights reserved.) The long path towards justice THE justice system in Mexico is on its knees. The innocent are imprisoned and criminals go free. The poor go to jail. The rich don't. Drug-trafficking, and theviolence it brings, may attract most international attention, but the flaws in the organisation of Mexico's courts and police affect far more people than the "narcos" ever do. The first step in fixing a problem is to admit you have one. "Our legal justice system has collapsed," says Patricia Villanueva, chief prosecutor in the southern state of Oaxaca. "It is obsolete," agrees Manuel Moreno Rivas, head of the state's judicial police, responsible for investigating crimes. That is why Oaxaca, along with half a dozen or so of Mexico's 32 states, is seeking to revolutionise its judicial system. Drawing on successful programmes in Chile and Costa Rica, it aims to move from a Napoleonic inquisitorial system, where prosecutors take most of the decisions and judges act largely as rubber stamps, toward a more British- or American-style adversarial system, in which oral arguments before a judge in court play a key role. According to Guillermo Zepeda, a researcher at CIDAC, a think-tank in Mexico City, 95% of crimes in Mexico fall under local jurisdiction. As a result, reforms at the state level are likely to have a more profound impact on the nature of crime and punishment in Mexico than action at the federal level. In any case, attempts to address structural problems at the federal level have stalled politically. The hope is that the patchwork effort to overhaul state systems will eventually "trickle up" to the federal level too. Of every 100 crimes in Mexico, it is estimated that only 20 or so are reported. In Oaxaca, only four or five of those 20 are actually investigated, Mr Moreno says, a figure broadly representative of the country as a whole. Furthermore, of the investigations that are opened, more than three-quarters are never resolved. There is also a strong selection bias. Because prosecutors have a weekly quota of indictments to meet, says Layda Negrete, a professor at CIDE university in Mexico City, the crimes which are prosecuted are either overwhelmingly minor ones or crimes where the perpetrator was caught redhanded. According to a 2003 survey by CIDE, over 60% of the prison population was caught in flagrante and more than half was there for minor, non-violent crimes. As a result, says Ana Magaloni, also of CIDE, Mexican jails are "stuffed full of poor people", while professional criminals are not caught. The underlying aim of the judicial reforms, which are broadly similar across the states seeking to implement them, is to increase transparency and efficiency, thereby supposedly prompting prosecutors and police to do a better job. Though there is some corruption, the main problem, according to Ms Magaloni, is incompetence. Everyone agrees on the need to set up training schemes for police, lawyers and judges, but this will not be easy. As Jose Antonio Caballero of Mexico City's National Autonomous University notes, at present there is no national bar association nor even a programme of accreditation for law schools. Torture If the state of Mexico's lawyers is bad, that of its police is arguably much worse. "It's a myth that the top level knows what's going on," Ernesto Lopez Portillo of the Institute for Security and Democracy in Mexico City says: "Real control rests with mid-level commanders." So when Mr Moreno and Ms Villanueva deny that prisoners are beaten or tortured, they may be in earnest, despite evidence to the contrary. Following his arrest in Oaxaca last year, Habacuc Cruz Cruz, a union organiser in the state, says that he was severely beaten and kept for three to eight days at a time in a tiny cell without light or ventilation, which measured just one square metre. Mr Moreno insists that such treatment no longer takes place; the penal system could not withstand the public outcry if it did, he says. But, as Ms Magaloni dryly comments, Mexicans have lost their capacity to react to scandal. Cases like Mr Cruz Cruz's no longer shock. Without a thorough overhaul of the police system as well, judicial reform will be futile, Mr Lopez Portillo argues. So far, only the northern state of Nuevo Leon has actually started implementing reforms. Cases involving minor crimes are now argued orally in front of a judge, instead of the judge reading mounds of papers alone in chambers. This, Mr Zepeda says, has already produced big gains in efficiency and equity. In Oaxaca, the state government hopes to pass legislation in the coming legislative term (ie, the next six months) to launch a five-year reform process leading to the formal installation of a new legal system. But even if all goes well at state level, the lack of change at the federal level could cause difficulties. Under a process called amparo--a challenge to the constitutionality of a local decision--almost any legal matter can be appealed to the federal courts. While only 2% of state cases at present go to amparo, Roberto Hernandez of CIDE says that this is sufficient to clog the federal system. Some two-thirds of appealed cases are dismissed by the federal courts, often on minor technical grounds. Unless the procedure is changed to one where appeals are possible only on specific legal grounds, there is a risk that, as today, anyone with the means could file for an almost limitless number of amparos, says Mr Hernandez, effectively neutering the state system. Juan de Jess Vasquez, a state appeals court judge in Oaxaca, believes the judicial reform plans represent a 180 degree change of course. But, he cautions, "many of us haven't been to law school in 25 years", so this would be difficult to achieve. The fruits of the reforms, he concedes, "are for my kids and grandkids". It will be a long time before Mexico has a justice system worthy of the name.