Laparoscopic repair of a stapler-induced lesion in the vena cava

Anuncio

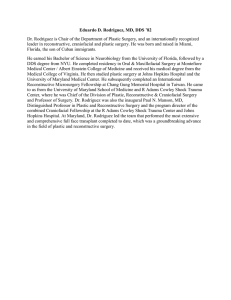

Rev Mex Urol 2014;74(3):190-192 ÓRGANO OFICIAL DE DIFUSIÓN DE LA SOCIEDAD MEXICANA DE UROLOGÍA, COLEGIO DE PROFESIONISTAS, A.C. www.elsevier.es/uromx Clinical case Laparoscopic repair of a stapler-induced lesion in the vena cava during laparoscopic nephrectomy E. I. Bravo-Castroa,*, J. G. Campos-Salcedob, A. Sedano-Lozanoc, J. J. Torres-Salazarc, J. J. Torres-Gómeza, J. A. Castelán-Martíneza, J. C. López-Silvestrec, M. Á. Zapata-Villalbac, C. E. Estrada-Carrascoc, H. Rosas-Hernándezc, C. Díaz-Gómezc, J. J. Islas-Garcíaa, J. Aguilar-Colmeneroa and I. A. Martínez-Alonsoa a Urology Speciality Residency, Escuela Militar de Graduados de Sanidad, Mexico City, Mexico b Urology Service Management, Hospital Central Militar, Mexico City, Mexico c Urology Service, Hospital Central Militar, Mexico City, Mexico KEYWORDS Nephrectomy; Laparoscopy; Lesion in vena cava; Laparoscopic repair; Mexico. Abstract The first reports on laparoscopic nephrectomy appeared more than 2 decades ago and the great benefits of this surgical technique have been demonstrated in relation to open or conventional surgery. As is the case with open surgery, laparoscopic surgery is not exempt from complications, which can range from slight undetected lesions to severe or catastrophic ones. We present herein the case of a patient that, while undergoing laparoscopic nephrectomy, had the complication of a lesion in the vena cava, which was resolved during the same procedure with no need to convert to open surgery. It is our opinion that the experience of the laparoscopic surgeon is important for resolving this type of problem. Laparoscopic surgery generally is converted to open surgery in the face of severe lesions. Depending on the case and the experience of the surgeon, such events can be repaired without the need for conversion. Palabras clave Nefrectomía; Laparoscopía; Lesión en vena cava; Reparación laparoscópica; Reparación laparoscópica de una lesión de vena cava producida por una engrapadora durante una nefrectomía laparoscópica Resumen La nefrectomía laparoscópica tiene más de 2 décadas, en las que empezaron los primeros reportes. Se han demostrado los grandes beneficios de esta técnica quirúrgica en relación a la cirugía abierta o tradicional. Al igual que la cirugía abierta, la cirugía laparoscópica no * Corresponding author at: Blvd. Manuel Ávila Camacho s/n, Lomas de Sotelo, Av. Industria Militar y General Cabral, Delegación Miguel Hidalgo, C.P. 11200, México D.F., México. Telephone: (01) 5557 3100, ext. 1704. Email: [email protected] (E. I. Bravo-Castro). Laparoscopic repair of the inferior vena cava in laparoscopic nephrectomy México. 191 está exenta de complicaciones, las cuales pueden ir de lesiones inadvertidas leves, hasta lesiones graves o catastróficas. Se presenta el caso de un paciente sometido a nefrectomía laparoscópica, donde se manifiesta como complicación una lesión en vena cava, haciéndose la reparación por esta misma vía sin necesidad de convertirla a cirugía abierta. Creemos que la experiencia del cirujano laparoscopista es importante para resolver este tipo de problemas. Las lesiones graves en cirugía laparoscópica generalmente la convierten en cirugía abierta; dependiendo del caso y la experiencia del cirujano, éstas pueden ser reparadas por la misma vía. 85-4542 © 2014. Revista Mexicana de Urología. Publicado por Elsevier México. Todos los derechos reservados. Introduction Since the first laparoscopic nephrectomy performed in 1991 by Clayman et al.1 for benign kidney disease, laparoscopy for malignant kidney diseases and healthy donor nephrectomy has rapidly increased. More extensive and complicated laparoscopic renal surgeries have been carried out in numerous urologic centers worldwide. Laparoscopic renal surgery has clear advantages over open surgery that include reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, a faster return to normal daily activities, and better cosmetic results.2 Nevertheless, laparoscopic renal surgery is associated with unique changes and complications, compared with open surgery. A complication range of 5% to 13.3% has been reported in various laparoscopic renal surgery case series, with a rate of conversion to open surgery of 4% to 7.5%.3-6 Vascular complications are common. In a meta-analysis of laparoscopic renal surgery complications in which different techniques were reviewed, venous trauma was found to be the most frequent vascular complication. It most often presented with a very high rate of conversion to open surgery, except in cases of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy.7 Vena cava injury can have a traumatic or iatrogenic origin. During nephrectomy, such lesions usually occur on the lateral wall. Customary management is primary repair with individual nonabsorbent sutures when the size of the lesion is less than 50% of the circumference; when lesions are greater than 50% of the circumference, they require a venous or peritoneal patch. Repair of posterior wall injury is more complex when there is massive destruction of the infrarenal inferior vena cava; its complete ligation is adequately tolerated.8 The aim of this report was to describe our experience with the laparoscopic management of injury detected in the inferior vena cava. the operation. The procedure began with the application of general anesthesia. A 16 Fr urethral catheter was placed, after which the patient was put in the right lateral decubitus position, supported by the articulated arms of the surgical table. Once the operating field was installed, a 1 cm incision lateral to the umbilicus was made to introduce the blunt-tip port. When adequate pneumoperitoneum (15 mmHg) was reached, the camera with a 30° lens was inserted. Diagnostic laparoscopy was carried out and 3 ports (one 10 mm and two 5 mm) were installed under direct vision: at the midpoint of the subcostal arch, midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the camera, and another over the iliac crest. A bipolar electrosurgical scalpel and radiofrequency electrocoagulation (Ligasure®) were used. First, the ipsilateral colon was separated in order to expose the retroperitoneum. En bloc dissection and freeing of the kidney initially located the ureter; it was sectioned and sealed with 10 mm clips. A more proximal dissection then reached the renal hilum, after which careful dissection and identification of the renal vein and artery were done. The renal artery was ligated using Hem-o-lok® and the renal vein was stapled using an Ethicon Endosurgery ENDO-GIATM ATW 45 mm stapler with a white reload for vascular use with 6 rows of staples. However, when the stapler was removed, it was found that the row of staples had not been adequately performed and there was an approximately 1 cm lesion in the lateral wall of the vena cava. Aspiration was immediately carried out, along with primary repair with 5-0 Prolene® double-armed sutures (fig.1). Adequate repair was verified. The procedure continued with the dissection of the upper pole, removing the surgical specimen. Hemostasis was verified, the ports were removed and a 1/8 drain was placed under direct vision. The port wounds were closed, ending the procedure. Case presentation Results A man in the sixth decade of life with no past medical history of chronic diseases was diagnosed with a right nonfunctioning kidney secondary to lithiasis. The proposed management was laparoscopic right simple nephrectomy. Surgery duration was 280 minutes and the repair time was 40 minutes. Quantified blood loss was 600 cc. Hospital stay was 5 days, postoperative pain was managed in the conventional manner, and the patient was ambulatory at 24 hours. Postoperative hemoglobin value was 9 g/dL. During the procedure one erythrocyte concentrate was applied. The drain was removed on the 4th day and the patient was released on day 6. His current follow-up at our service shows adequate control. Procedure description After receiving the diagnosis and having the procedure explained to him, the patient gave his informed consent for 192 E. I. Bravo-Castro et al highly experienced in laparoscopic procedures and always open to the possible necessity of procedure conversion in order to have successful repair; another determining factor is the hemodynamic condition of the patient, never letting the laparoscopic approach compromise the stability of the patient and always being aware of the possibility of conversion; other important factors are having an adequate hospital infrastructure in relation to laparoscopic and surgical material and having the support of a blood bank, if needed; and an essential factor is adequate surgical team coordination, completely synchronized with the surgeon, so that there is active collaboration during the procedure. Figure 1 Intraoperative image during primary repair. Discussion Over the past 20 years, laparoscopy has had a great impact on the management of patients presenting with genitourinary problems thanks to its many advantages, such as reduced blood loss, less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, and rapid return to normal daily activities. However, it requires a learning curve, as well as a command of the complications derived from the procedure, such as problems related to trocar insertion and carbon dioxide pressure.3 The learning curve varies, depending on the procedure to be performed. In the case of nephrectomy, at least 50 are considered necessary; as a minimum, one procedure a week for the first year of training. It is well known that the number of complications decrease as experience increases.3 In a study reporting on the first 100 cases of laparoscopic nephrectomy, the complication rate was approximately 13.3%; it decreased to 3.6% as the procedures continued to be performed. 3 In a meta-analysis published on the experience of different laparoscopic procedures, the most frequent intraoperative complication was blood loss at 1.4%; intestinal trauma was found in fewer than 0.5% of the cases, and trauma to a solid organ in less than 0.5%.7 A case series on complications related to nephrectomy stated that one of the complications produced by bleeding was due to poor technique in closing the stapler over the renal vein and required conversion to open surgery in order to be controlled.7 Finally, we can conclude that despite the fact that laparoscopic nephrectomy is an ideal method for the surgical management of renal pathology in selected cases, it is not exempt from complications; the most common one is intraoperative bleeding due to vascular injury. There are various factors that determine the possibility of laparoscopic repair: initially the laparoscopic urologic surgeon should be Conclusions In our experience with this patient there were various factors that determined the success of the primary repair, the most significant of which was the experience of the laparoscopic surgeon in the management of such lesions. Conflict of interest The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Financial disclosure No financial support was received in relation to this article. References 1. Clayman RV, Kavoussi LR, Soper NJ, et al. Laparoscopic nephrectomy: initial case report. J Urol 1991;146:278. 2. Simon SD, Castle EP, Ferrigni RG, et al. Complications of laparoscopic nephrectomy: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Urol 2004;171(4):1447-1450. 3. Vallancien G, Cathelineau X, Baumert H, et al. Complications of transperitoneal laparoscopic surgery in urology: review of 1,311 procedures at a single center. J Urol 2002;168:23. 4. Soulie M, Seguin P, Richeux L, et al. Urological complications of laparoscopic surgery: experience with 350 procedures at a single center. J Urol 2001;165:1960. 5. Siqueira TM Jr., Kuo RL, Gardner TA, et al. Major complications in 213 laparoscopic nephrectomy cases: the Indianapolis experience. J Urol 2002;168:1361. 6. Fahlenkamp D, Rassweiler J, Fornara P, et al. Complications of laparoscopic procedures in urology: experience with 2,407 procedures at 4 German centers. J Urol 1999;162:765. 7. Pareek G, Hedican SP, Gee JR, et al. Meta-analysis of the complications of laparoscopic renal surgery: comparison of procedures and techniques. J Urol 2006;175(4):1208-1213. 8. Asensio JA, Navarro Soto S, Forno W, et al. Lesiones vasculares abdominales. El desafío del cirujano traumatológico. Cirugía Española 2001;69(4):386-392.