Parenting and Adolescents` Self-esteem: The Portuguese Context

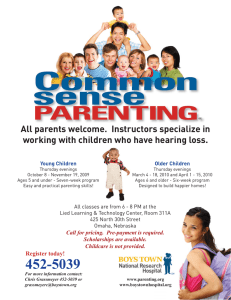

Anuncio