Alzheimer`s Disease: A practical guide for families

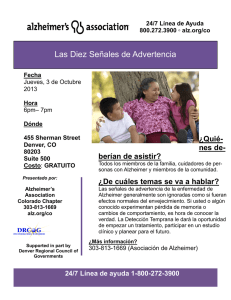

Anuncio