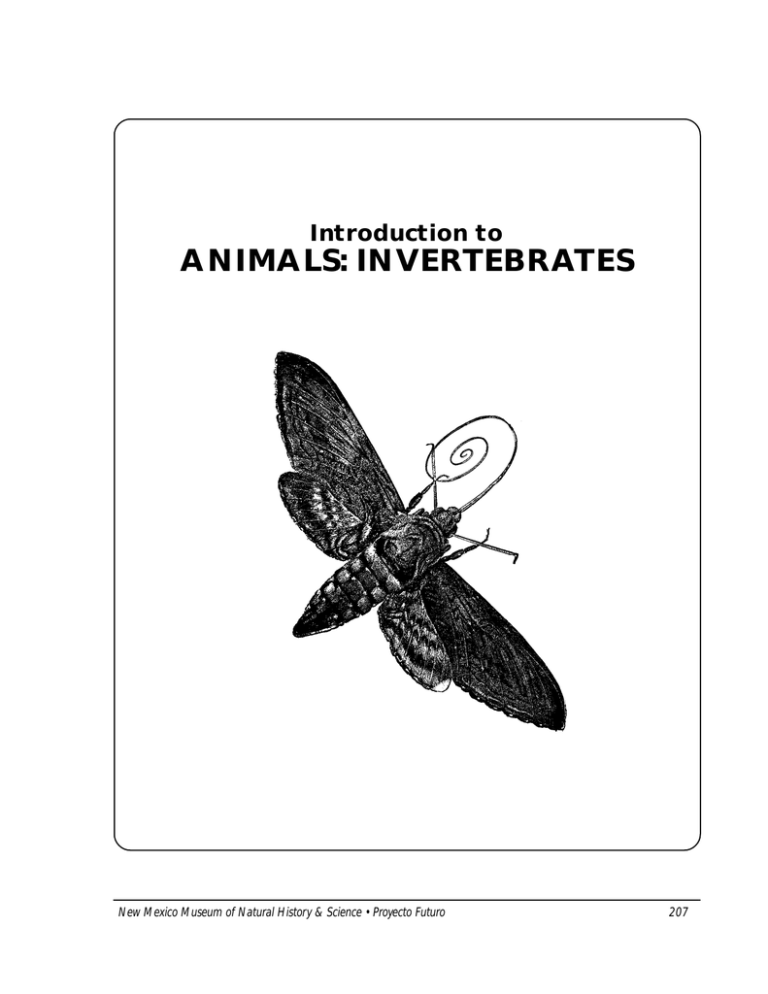

animals: invertebrates - New Mexico Museum of Natural History

Anuncio