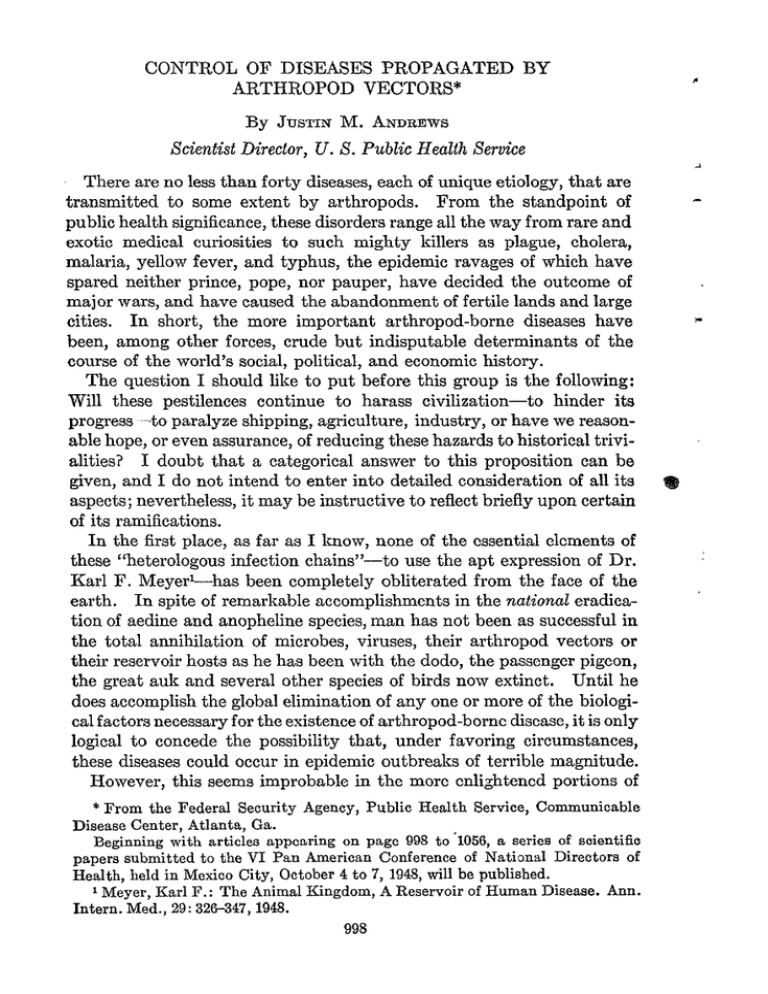

CONTROL OF DISEASES PROPAGATED BY ARTHROPOD

Anuncio

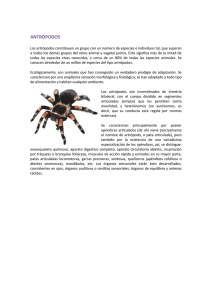

CONTROL OF DISEASES PROPAGATED ARTHROPOD VECTORS” BY By JUSTIN M. ANDREWS Scientist Director, U. X. Public Health Service There are no less than forty diseases, each of unique etiolo,gy, that are transmitted to some extent by arthropods. From the standpoint of public health significance, these disorders range al1 the way from rare and exotic medical curiosities to such mighty killers as plague, cholera, malaria, yellow fever, and typhus, the epidemic ravages of which have spared neither prince, pope, nor pauper, have decided the outcome of major wars, and have caused the abandonment of fertile lands and large cities. In short, the more important arthropod-borne diseases have been, among other forces, crude but indisputable determinants of the course of the world’s social, political, and economic history. The question 1 should like to put before this group is the following: Will these pestilentes continue to harass civilization-to hinder its progress-to paralyze shipping, agriculture, industry, or have we reasonable hope, or even assurance, of reducing these hazards to historical trivialities? 1 doubt that a categorical answer to this proposition can be given, and 1 do not intend to enter into detailed consideration of al1 its aspects; nevertheless, it may be instructive to reflect briefly upon certain of its ramifications. In the first place, as far as 1 know, none of the essential elements of these “heterologous infection chains”-to use the apt expression of Dr. Karl F. MeyerLhas been completely obliterated from the face of the earth. In spite of remarkable accomplishments in the national eradication of aedine and anopheline species, man has not been as successful in the total annihilation of microbes, viruses, their arthropod vectors or their reservoir hosts as he has been with the dodo, the passenger pigeon, the great auk and severa1 other species of birds now extinct. Until he does accomplish the global elimination of any one or more of the biological factors necessary for the existence of arthropod-borne disease, it is only logical to concede the possibility that, under favoring circumstances, these diseases could occur in epidemic outbreaks of terrible magnitude. However, this seems improbable in the more enlightened portions of * From the Federal Security Agency, Public Health Service, Communicable Disease Center, Atlanta, Ga. Beginning with articles appearing on page 998 to ‘1056, a series of scientific papers submitted to the VI Pan Ameriean Conference of National Directora of Health, held in Mexico City, October 4 to 7, 1948, will be published. 1 Meyer, Karl F.: The Animal Kingdom, A Reservoir of Human Disease. Ann. Intern. Med., 29: 326-347,1943. 998 [November 19481 L * 8 * ARTHROPOD VECTORS 999 the world where the depredations of diseases spread by insects, ticks and mites appear to have Iessened materially during rece& years. With the knowledge now available, it is hard to visualize the BIack Death again possessing London or other major cities of Europe or that yellow fever could return to wipe out 70 per cent of the white residents of Ameritan communities% British and Ameritan troops have returned only recently from a war, much of which was fought in the tropics, where malaria seriously threatened though it never actually determined the outcome of military operations. The United States of America has contained, with scant evidente of transmission from these sources, the impact of probably a hundred thousand or more repatriated malaria-carrying service men and women, many of whom returned to traditionally endemic areas. The Allied Forces in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations looked squarely into the face of an incipient OId World typhus epidemic in Italy-and supSince the war, an epidemic of cholera pressed it calmly and effectively. in Egypt has been nullified far short of the destructive proportions it would probably have attained a few decades ago-and, what is even more impressive, there appear to have been no secondary outbreaks stemming from the Egyptian experience. Numerous Latin Ameritan countries reported at the Fourth International Congresses of Tropical Medicine and Malaria the extirpation of Aedes aegypti and, pari passu, of dengue and urban yellow fever from within their borders; others are undertaking similar programs with confidence. Chile indicates that malaria has been eliminated from that country. Anopheline eradication programs are under way in Sardinia and Cyprus-and are planned for other islands. We feel that another three years will see the end of malaria as an endemic disease in our country. TheSe accompIishments and prospects should not be viewed with stultifying complacence nor should they engender a faIse sense of security. They merely mark progress toward a distant goal. Preventive medicine has come a long way since “experts” gravely argued the bedside range of the infectivity of yellow fever patients,” expounded the so-called “Law of Malaria,“3 and seriously advocated perfume and tobacco-smoking as plague preventives.4 ’ The epoch of arthropodal epidemiology portended by Mason’s demonstration of íYaria larvae in mosquitoes (1S77)6 and firmly established by 2 Keating, J. M.: A History of the Yellow Fever. The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878 in Memphis, Tenn. Memphis pp. 454 + VIII, 1879. s Scott, H. Harold.: A History of Tropical Medicine. Vol. 1, pp. 648 + XVIII, London. 4 Ibid., Vol. II, pp. 570 + IV. 6 Manson, P.: Filaria sanguinis hominis and Certain New Forma of Parasitic Diseases. London, 1883. 1000 PAN AMERICAN SANITARY BUREAU [November Smith and Kilbourne’s revelation of the tick transmission of Texas fever (1893)ô has been one of brilliant discovery. In rapid succession, the essential facts were elucidated concerning the transfer of malaria, yellow fever, plague, typhus, and a host of lesser ills spread by arthropods. These expositions have provided the basis for a cooperative assault by the sanitarian and the therapeutist in obstructing the transmission of these diseases. It is the application of Ibis technical knowledge, plus administrative proficiency, that has made possible the achievements mentioned above. In the natural evolution of preventive medicine, these efforts have usually been restricted at first to so-called “Control” activities, the primary intent being to halt the progress of an existing disease. A natural extension of this objective has been to devise and execute measures which preclude its reappearance, that is, to “prevent” disease. To this lexicon of preventive medicine, Dr. Fred Soper and his associates have made an audacious addition which is undoubtedly here to stay. The verb “eradicate” is undoubtedly a fugitive from the jargon of journalism, but Dr. Soper and his cohorts have, by ‘their own acts, invested this superlative with a new dignity and verity.7, a+g Already it has legitimate application on a national scale; extension to hemispherical inclusiveness is contemplated. It is not impossible that even in our own lifetime we may see the word used with studied seriousness to comprehend the global nullification of one or more diseases. In theory, the eradication of arthropod-borne diseases can be accomplished by the extermination either of the causative agent or the vector, the choice depending, presumably, upon which of the two can be more effectively and economically eliminated. The latter procedure, vector eradication, is exemplified by the well-known accomplishments of Dr. Soper and his colleagues.** g Without doubt, it is the method of choice when feasible, as it is probably easier to prevent or deal with the re-entry into clean areas of arthropod vectors than infected humans. It is particularly applicable to geographic or biological islands where the problems of infiltration and reintroduction are minimal, though, as has been dem6 Smith, T., and Kilborne, F. L.: Investigations into the nature, causation and prevention of Texas or southern cattle fever. U. S. Dept. Agrie., Bur. Animal Industry, Bull. No. 1. Washington Gov. Print. Office, pp. 301, 1893. r Soper, F. L., and Wilson, D. B.: Species Eradication. A Practica1 Goal of Species Reduction in the Control of Mosquito-borne Disease. J. Nat. Mal. soc., 1: 5-24, 1942. * Soper, Fred L.; Wilson, D. Bruce; Lima, Servuio; and Antunes, Waldemar Sa: The Organization of Permanent Nation-wide Anti-Aedes Aegypti Measures in Brazil. pp. 137. New York. 1943. 9 Soper, Fred L., and Wilson, D. Bruce: Anopheles gambiae in Brasil, 1930 to 1940. pp. 262 + XVIII. New York. 1943. 19-481 L v ARTHROPOD VECTORS 1001 onstrated, it can be used successfully over extended continental areas.a vg* lo Thusfar, attempts at the eradication of arthropod-borne diseases solely by chemical or biological destruction of the etiologic agent have not been as successful as efforts at its exclusion, e.g. yellow fever from the United States. This has been due to the imperfections of chemotherapeutics, antibiotics and vaccines, and to the great difhculty of obtaining thorough application on a wide enough scale. Nevertheless, the role of microbicides, viricides and vaccines in reducing reservoirs of infection for arthropods is already considerable and is gaining steadily in importance. When used in conjunction with insecticides or acaricides, these disinfective measures give promise of disease eradication. Thus, if vector density and the frequency of human carriers can be reduced simultaneously, a point will be reached ultimately where the statistical probability of transmission is nil, and the disease disappears. This is the principie on which we are basing our malaria eradication program in the U. S. A. It is apparent that certain diseases spread by arthropods cannot be eradicated because they are perpetuated in arthropods or other lower animals. These include yellow fever, plague, relapsing fever, tularemia, the vira1 encephalitides, certain leishmanial infections, and severa1 of the rickettsial diseases. Their prevalence can, of course, be reduced markedly by attacking the vector which transmits from reservoir host to man, and, where the reservoir species is domestic, by its destruction, treatment or immunization. In countries where lower animal reservo% do not exist, the disease can be excluded by appropriate foreign quarantine measures. Certain other diseases, such as malaria, while readily eradicable in some places present formidable difliculties in others because of the ignorance, poverty, and vast human reservoirs of infection involved, for example, in tropical Africa, India, South China, etc. One wonders what the social and economic consequences might be if the burden of communicable disease were lifted from such populations ! Probably the greatest deterrent to eradication of arthropod-born sickness is world warfare. Global travel, especially by air, during peace times is a constant threat to such projeets but, relative to large scale miliCertainly there is no more tary operations, it is minor in importance. challenging test of the techniques of preventive medicine than the conditions of prolonged military campaign and their inevitable sequelae, When, to the normal and unavoidable disease hazards of armed conflict, is added the grim specter of deliberate biological warfare (which might Io Soper, F. L.: Species Sanitation as AppIied to the Eradication of (a) and Invading or (b) an Indigenous Species. Presented before the Fourth Inter. Gong. Trop. Med. and Malaria. Washington. May, 1948. 1002 OFICINA SANITARIA PANAMERICANA [Noviembre include the dissemination of diseases spread by arthropods), the possibilities for halting progress in the eradication of these infections is evident. To return to the question 1 raised earlier, my provisional answer would be about as follows: Barring world conflicts, especially those in which the end would seem to justify such ruthless means as biological warfare, there is every reason to believe that the present trend of arthropod-borne diseases should continue downward. None of them need ever threaten civilization again where the means and the will exist to control and prevent them. Some of these diseases appear to be susceptible to eradicative technology, certainly within the more advanced countries of the world. phases of t,hese proIt is to discuss the technical and administrative cedures that we have met together. May 1 thank you in advance for 1 trust that you will enter heartily into the discusyour contributions. sion of the following papers and that the occasion will be mutually stimulating and instructive to us all. CONTROL DE LAS ENFERMEDADES TRANSMITIDAS POR ARTROPODOS (Sumario) Existen por lo menos cuarenta enfermedades, cada una de etiologfa distinta, en cuya transmisión intervienen en algún grado los artr6podos. Desde el punto de vista de significación sanitaria, estos padecimientos varian desde raras y exóticas curiosidades m6dicas hasta los temibles azotes que representan la peste, el c6lera, el paludismo, la fiebre amarilla y el tifo, de cuyos estragos no se libra nadie y que han determinado el resultado de importantes guerras y causado el abandono de tierras fértiles y grandes ciudades. En resumen, las m& importantes enfermedades de transmisión por artrópodos han sido, entre otras fuerzas, crudas pero indiscutibles determinantes del curso de la historia social, política y económica del mundo. Ninguno de los elementos esenciales de estas “cadenaa heterólogas de infecci&“-para usar la acertada expresión del Dr. Karl F. Meyer-ha sido eliminado completamente de la faz de la tierra. A pesar de notables adelantos en la erradicación nacional de las especies abdicas y anofelinas, el hombre todavia no ha logrado la exterminación de los microorganismos y virus, o de sus vectores artrópodos o huéspedes reservorios, tal como ha hecho en el caso del dido, la paloma silvestre Ectopistes migratorius, el gran “auk” y otras especies de aves hoy extintas. Mientras no se consiga la eliminación mundial de uno o m8s de los factores biológicos necesarios para la existencia de las enfermedades transmitidas por artrópodos, es lógico admitir la posibilidad de que, en circunstancias favorables, estas enfermedades se presenten en forma de brotes epidbmicos de terrible magnitud. Sin embargo, esto no parece probable en las regiones más adelantadas del globo, donde los estragos producidos por las enfermedades transmitidas por insectos, garrapatas y Icaros parecen haber disminuido en años recientes. Las tropas británicas y americanas regresaron no hace mucho de una guerra librada en gran parte en los trópicos, donde el paludismo constituyó una grave amenaza para las operaciones militares, aun cuando nunca lle,@ a determinar su resultado. Los Estados Unidos de Norte América han podido contener, con pocas evidencias de contagio proveniente de esa fuente, el impacto de probablemente 19-4~1 ARTRÓPODOS VECTORES 1003 cien mil o más hombres y mujeres del servicio militar portadores del paludismo, muchos de los cuales regresaron a zonas tradicionalmente endemicas. En el Teatro Mediterráneo de Operaciones, las Fuerzas Aliadas confrontaron y dominaron en Italia, una epidemia incipiente de tifo. Terminada la guerra se logro vencer una epidemia de cólera en Egipto, mucho antes de que alcanzara proporciones destructoras. Numerosos países latinoamericanos comunicaron en el Cuarto Congreso Internacional de Medicina Tropical y Paludismo, haber extirpado de su territorio el Aëdes aegypli, yen consecuencia, el dengue y la fiebre amarilla urbana, y otros han emprendido programas similares con plena confianza de éxito. En Chile el paludismo ha sido eliminado y ya se han iniciado campañas de erradicación anofelina en Cerdeña y Chipre, proyectándose actividades semejantes para otras islas. Consideramos que en tres años mas veremos desaparecer de nuestro país el paludismo como enfermedad endémica. La 6poca de la epidemiología artropódica vislumbrada por la demostración por Manson de larvas de filarias en mosquitos (1877), y establecida en firme con la comprobación por Smith y Kilbourne de la transmisión de fiebre de Texas por la garrapata (1893), ha sido una de descubrimientos brillantes. En sucesión rápida fueron descubiertos los hechos fundamentales sobre la transmisión del paludismo, la fiebre amarilla, la peste, el tifo y de gran número de males de menor importancia transmitidos por artrópodos. Estos descubrimientos han constituido la base de una lucha conjunta del higienista y el terapeuta para evitar la propagación de estas enfermedades. La aplicación de estos conocimientos técnicos, además de Ia eficiencia administrativa, han hecho posibles las realizaciones arriba anotadas. En el desenvolvimiento de la medicina preventiva, al comienzo, estos esfuerzos estuvieron generalmente limitados a las llamadas actividades de “control”, siendo su primer objetivo detener la propagación de una enfermedad existente. Como extensión lógica de este objetivo, se ha procedido luego ala invención y ejecución de medidas que eviten su reaparición, es decir, que “prevengan” la enfermedad. Al léxico de la medicina preventiva, el Dr. Fred Soper y sus colaboradores agregaron el verbo “erradicar”, que indudablemente formará parte permanente del vocabulario. Este vocablo ya tiene aplicación legitima en escala nacional; se contempla su extensión ala aplicación continental, y es posible que aun en nuestros tiempos se le llegue a emplear, con toda seriedad, para abarcar la extirpación global de una o mas enfermedades. En teorfa, la erradicación de enfermedades transmitidas por artrópodos puede realizarse mediante el exterminio, ya sea del agente causante o del vector, de acuerdo con la relativa eficacia y economía con que se pueda eliminar este o aquel. Del último procedimiento, la erradicación del vector es particularmente aplicable a las islas geograficas o biológicas, donde los probIemas de infiltración y reintroducción son mfnimos, aun cuando, como ya se ha demostrado, es posible su empleo con buenos resultados, en extensas zonas continentales. Hasta el presente, en la lucha contra las enfermedades transmitidas por artrópodos Ias medidas que tienen como bnico objeto la destrucción del agente etiológico por medios qufmicos o biológicos no han dado tan buenos resultados como las tendientes a su exclusión, como ha sucedido con la fiebre amarilla en los Estados Unidos. Esto se debe a.las imperfecciones de los agentes quimioterapéuticos y antibióticos y de las vacunas, asf como a las grandes dificultades inherentes a su aplicación eficaz en una escala suficientemente extensa. Sin embargo, el papel de los microbicidas, viricidas y vacunas en la reducción de los reservorios de infecci6n de los artrópodos ha llegado a ser importante, y sigue aumentando constantemente en valor. Empleados en combinación con los insecticidas o acaricidas, 1004 OFICINA SANITARIA PANAMERICANA [Noviembre 19.JS] estos recursos de desinfección son prometedores de éxito en la erradicación de las enfermedades infecciosas. Asf, pues, si se reducen simultáneamente la densidad del vector y la frecuencia de portadores humanos, se llega a un punto en que las probabilidades estadfsticas de transmisión son nulas, y desaparece la enfermedad. Sobre este principio hemos basado en los Estados Unidos nuestro programa de erradicación del paludismo. Es evidente que hay ciertas enfermedades propagadas por artrópodos que no pueden ser erradicadas porque se perpetúan en ellos o en otros animales inferiores, y las que incluyen la fiebre amarilla, peste, fiebre recurrente, tularemia, las encefalitis virales, ciertas formas de leishmaniasis, y algunas de las rickettsiasis. Sin embargo, la incidencia de estas enfermedades puede reducirse notablemente atacando al vector intermediario entre el huesped y el hombre, o cuando la especie reservorio es doméstica, mediante su destrucción, tratamiento o inmunización. Probablemente el mayor obstaculo a la erradicación de las enfermedades transmitidas por artrópodos es la guerra. En tiempos de paz, el tr&nsito global, especialmente el aéreo, es una constante amenaza para esos programas, pero resulta de menor importancia comparado con las operaciones militares en gran escala. Ciertamente no existe mas dura prueba para las técnicas de medicina preventiva que la representada por las condiciones de prolongada campaña militar y sus inevitables secuelas. Cuando a los riesgos normales e inevitables de enfermedad que representa el conflicto armado, se añade el espectro funesto de la guerra biológica *deliberada (que puede incluir la diseminación de enfermedades propagadas por .artrópodos), se hace evidente la posibilidad de que se cohiba la erradicación de estas infecciones. En ausencia de conflictos mundiales, y sobre todo aquellos en que el fin parezca justificar medidas extremas tales como la guerra biológica, existe toda razón para pensar que la incidencia de las enfermedades transmitidas por artropodos continuar& en descenso. Ninguna de ellas habrfa de amenazar nuevamente ala civilización en aquellos lugares donde existan recursos y voluntad para controlarlas y prevenirlas.