Valley Confidential/ A Conversation with Rolando

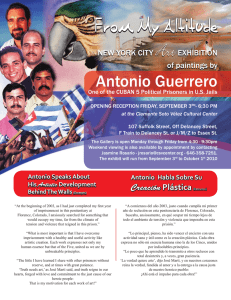

Anuncio