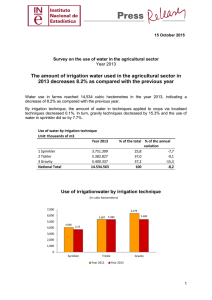

Water ethics

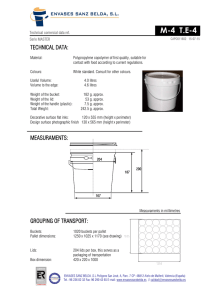

Anuncio