Mayores que viven solos: una panorámica a partir de los censos de

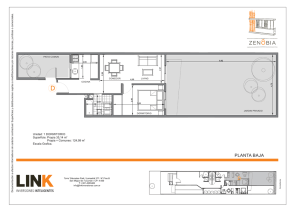

Anuncio