El Bienestar Animal y la Calidad de Carne de novillos en

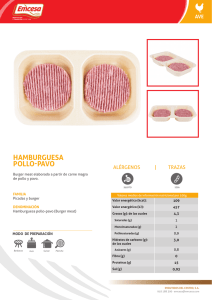

Anuncio