Alcott, Louisa May ``LittleWomen``-Xx-En-Sp.p65

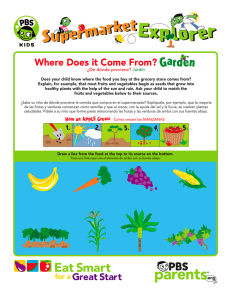

Anuncio