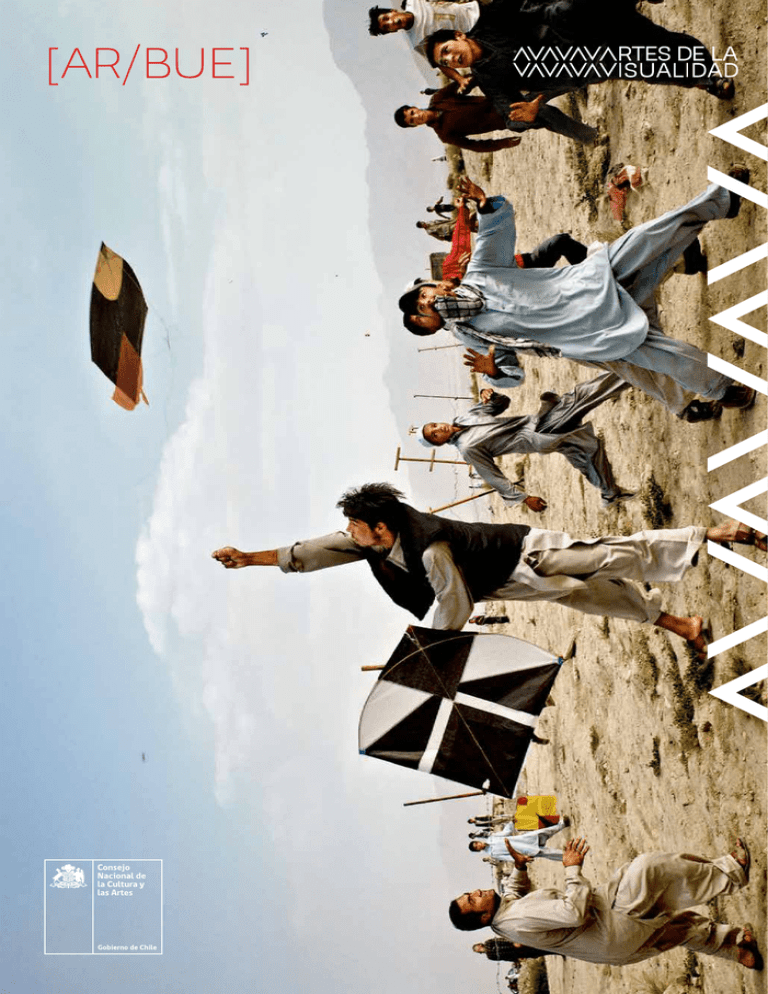

Periódico Artes Visuales - Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes

Anuncio