Mariely Colon A Brief History of Female Sexuality Paraphilia… and

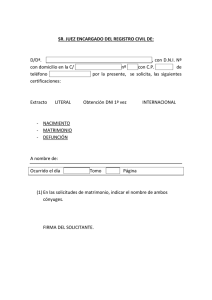

Anuncio