Spanish as Foreign Language Teachers` conceptions of assessment

Anuncio

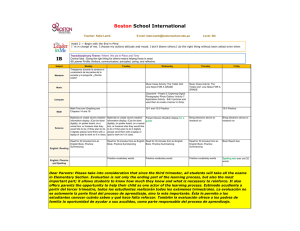

This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie Spanish as Foreign Language Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Ana Remesal Universidad de Barcelona, Spain Gavin T.L. Brown University of Auckland, New Zealand Introduction This study intends to fill a gap in current research on conceptions of assessment. Indeed, conceptions of assessment have been focus of systematic research in the last decade in different cultural contexts (e.g., Brown, Kennedy, Fok, Chan & Yu, 2009; Brown, Lake & Matters, 2011; Coll & Remesal, 2009; Delandshere & Jones, 1999; Remesal, 2011). These studies refer mostly to in-service teachers, both active in primary or secondary education. Other recent studies, such as Brown & Remesal (2012) turned attention to prospective teachers. However, up to now, we have very little information-if any at allabout teachers’ conceptions of assessment in educational contexts other than compulsory or basic schooling. We gathered data from teachers of Spanish as Foreign Language (ELE) working in four different educational contexts: compulsory school, extra-school teaching, adult education, and in-company training. Research method and design We presented a questionnaire with a positively packed rating scale (Brown, 2004) to the members of an online professional community of teachers of ELE (Comunidad Todoele, http://www.todoele.net/). 7500 teachers altogether were invited to respond to the questionnaire. The questionnaire got a response ratio of 7%; hence, the sample is 492 respondents (margin of error = 4.72%), in a three month period with three reminder invitations. Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in table 1. The questionnaire was built around a theoretical model of conceptions of assessment, drawn from a previous interpretive research (Remesal, 2006). This model rests on a definition of conceptions as the subjective sum of individual beliefs, which, in turn, are assumptions about objects and phenomena that people take as true (often without intellectual contrast) (Green, 1971; Pajares, 1992). The model refers to four basic dimensions within a bipolar continuum of conceptions. It states that conceptions about assessment are the result of a combination of beliefs about how assessment affects (a) teaching, (b) learning, (c) the certification of learning, and (d) the account giving of teaching. Hence, depending on the combination of particular beliefs, a teacher’s conception can be defined as more inclined towards understanding assessment as an This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie “instrument for regulation of educational processes” or rather as an “instrument for societal control”. The following variables were considered for further comparison: professional practice context and type of initial training. Results Participants in this study were asked to report personal characteristics about themselves (Table 1). The sample was characterised by teachers who were predominantly female, middle-aged, and with considerable teaching experience. The majority had their initial training in linguistic (e.g., translation, philology, linguistics) rather than educationoriented (e.g., pedagogy, didactics, psychology) disciplines. Just over half taught in adult-level contexts (e.g., higher education or in businesses), while the remainder taught children and adolescents in schools or after-school contexts. Confirmatory factor analysis of the data was used to evaluate the proposed 6 factor, bifactoral structure (Figure 1). In this model, beliefs about assessment refer to four aspects of the teaching and learning process that may be affected by the participant’s sense of whether assessment regulates or does not regulate them. The factors then were teaching, learning, certifying of learning, and accountability of teaching and two tendencies of using assessment, either pro- or anti-formatively. Each item is predicted by one of these aspects and tendencies. The fit of the model was acceptable (χ2=1040.39, df=486, [χ2/df=2.141, p=.14]; CFI=.81; gamma hat=.94; RMSEA=.048, 90% CI=.044-.052; SRMR=.052). While not every path was statistically significant, the combined weight of paths produced percentage of variance explained ranging from 2% to 47% (M=25%, SD=12.5%) (see Table 2). Mean scores for each factor were calculated by averaging all items contributing to the factor (Table 3). These values indicated that the sample as a whole endorsed the regulation of learning most, though the differences among the four aspects were small. The Pro-Formative tendency was much more strongly endorsed than the Anti-Formative tendency. Beliefs concerning the formative regulation of learning and teaching were endorsed most strongly; and teachers gave the weakest agreement to the Anti-Formative tendency of these same two aspects. As a whole, then, the teachers’ conceptions of assessment were positive towards Formative uses of assessment for the improvement of teaching and learning. In order to carry out a multiple analysis of variance of the effect of key demographic variables on conceptions, eight interactive factor scores were used (i.e., Learning-Pro, Teaching-Pro, Accountability-Pro, Certifying-Pro, Learning-Anti, Teaching-Anti, Accountability-Anti, and Certifying-Anti). The predictor variables used were initial training and working context (i.e., students were either children/adolescents or adults). Statistically significant differences were found only for the main effect of working context (Wilks’ λ=.96; F(8,478)=2.71, p=.006) (i.e., interaction and main effect for training were not statistically significant). Inspection of univariate differences for the eight factor scores showed that statistically significant differences existed for only three This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie factors (i.e., Accountability-Anti, p=.006, d=.26; Certifying-Anti, p=.031, d=.20; and Learning-Anti, p<.001, d=.38). In all three cases, teachers in adult contexts gave lower scores, though the differences were small to moderate. Multi-group confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to determine whether the measurement model was statistically equivalent across the two working contexts. Constraining the measurement weights to be the same for the two groups resulted in a difference in CFI=.011 which exceeds the standard of <.01, supporting the conclusion that the two groups responded to the inventory in different ways. Thus, we can conclude that teachers of Spanish in these two different contexts are samples of two different populations. Further analyses of the regression weights and inter-factor correlations is needed to understand how the teaching context impacts beliefs about assessment. Discussion and conclusion The results of this study show that, as proposed by the original model (Remesal, 2006), teacher beliefs about assessment are a consequence of two interacting elements; that is, teacher beliefs about the effects of assessment and teacher’s evaluation as to whether assessment may have formative or non-formative uses. On the whole, the teachers of Spanish as a foreign language conceived of assessment primarily in terms of its regulating effects on teaching and learning and were strongly positive towards formative assessment purposes. In other words, they agreed mostly that assessment existed to serve the improvement of teaching and learning. Differences based on context of work identified that those working in adult contexts were less positive about the nonformative aspects of assessment, a result that may be explained by the greater responsibility of care for students that teachers in schooling contexts are expected to exercise. This result is coherent with the theoretical model which declares the twofold functional nature of assessment in the basic school system (Remesal, 2011), which by default imposes both, formative and non-formative (i.e., accrediting and accountability) purposes of assessment. Within schooling contexts, teachers have to accept that assessment results are also used to evaluate students, monitor teacher effectiveness, and judge school quality. In contrast, it appears that teachers working outside the basic school system have a lesser attachment or commitment to non-formative purposes; perhaps this arises because adult learning and teaching is more driven by interest and personal motivation and hence, attracts a lesser sense of accountability and evaluation. Further analysis of the non-equivalent aspects of the measurement model across working contexts is needed to see if further insights can be gained. Nonetheless, this study provides internal validation evidence for the questionnaire and advances our understanding of the contingencies in teachers’ belief systems about assessment. Acknowledgements This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie Ana Remesal and Gavin Brown want to acknowledge the contribution of Patrick S.G.Kerr to the analysis of the reported data. References Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Measuring attitude with positively packed self-report ratings: Comparison of agreement and frequency scales. Psychological Reports, 94, 1015–1024. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.94.3.1015-1024 Brown, G. T. L., Kennedy, K. J., Fok, P. K., Chan, J. K. S., & Yu, W. M. (2009). Assessment for student improvement: Understanding Hong Kong teachers’ conceptions and practices of assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 16(3), 347–363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09695940903319737 Brown, G. T. L., Lake, R., & Matters, G. (2011). Queensland teachers’ conceptions of assessment: The impact of policy priorities on teacher attitudes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 210–220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.003 Brown, G.; Remesal, A. (2012). Prospective teachers’ conceptions of assessment: a cross-cultural comparison. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, vol.15 (1, onlinefirst). Coll, C., & Remesal, A. (2009). Concepciones del profesorado de matemáticas sobre la evaluación del aprendizaje en la educación obligatoria: dimensiones y funciones. [Mathematics teachers’ conceptions of learning assessment in compulsory education: dimensions and functions]. Infancia y Aprendizaje,32(3), 391–404. Delandshere, G., & Jones, J. H. (1999). Elementary teachers’ beliefs about assessment in mathematics. A case of assessment paralysis. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 14(3), 216–240. Green, T. F. (1971). The activities of teaching. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), pp. 307–332. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307 Remesal, A. (2006). Los problemas en la evaluación del área de matemáticas en la educación obligatoria: perspectiva de profesores y alumnos. Tesis Doctoral presentada en la Universidad de Barcelona. Director: Dr.César Coll Salvador. Remesal, A. (2011). Primary and secondary teachers’ conceptions of assessment: A qualitative study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 472–482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.TATE.2010.09.017 This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie Figure 1. Bifactoral measurement model of 492 Spanish as a Foreign Language (ELE) teachers’ responses to inventory This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample Category Age <35 35-50 >50 N % 160 32 233 47 100 20 Sex male female 105 21 288 79 Teaching experience <2 years 2-5 years 5-10 years >10 years 52 96 110 235 11 19 22 48 Initial training Linguistic-oriented 303 62 Educational-oriented 138 38 Student addressees Children-adolescents 222 45 Adults 270 55 This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie Table 2. Item statistics by predictor factors item ac01 ac02 ac03 ac04 ac05 ac06 ac07 ac08 ac09 Spanish Ante unos malos resultados de un grupo de alumnos, la mejor opción es bajar el nivel o incluso repetir la evaluación Una ‘bajada de nivel’ y hacer la ‘vista gorda’ nunca es la solución cuando nos encontramos con malos resultados de evaluación en una clase El avance de los alumnos siempre se debe valorar con el mismo rasero para todos, según los objetivos del curso planteados El punto de partida individual es la referencia imprescindible para valorar adecuadamente el avance de cada alumno Es preferible comunicar los resultados en forma estrictamente numérica, para evitar malentendidos Las calificaciones numéricas (0-10, 6-1, 115,…), o categoriales básicas (A,B,C; aprobado, suspenso…) son, por lo general, poco informativas Para aprobar, el alumno debe alcanzar un dominio mínimo, indicado en el currículo oficial vigente Para aprobar, el alumno debe demostrar que ha avanzado bastante desde su punto de partida al inicio del curso La comunicación de resultados siempre debe ser pública para que cada alumno se ubique en el grupo-clase ac10 La comunicación de resultados debe ser siempre privada para evitar comparaciones ap01 Los ‘exámenes sorpresa’ son un buen elemento English In face of bad assessment results, the best option is to lower the standards or even to repeat the test Lowering standards and blinking an eye are never the solution to face bad assessment results in a course Students’ learning progress must be always measured with the same scale for everyone, according to the course objectives The individual starting point is an indispensable reference to properly evaluate the individual student’s progress It is always better to communicate assessment results in a numerical form, in order to avoid misunderstandings Numerical grading or basic categories are, generally speaking, uninformative. In order to pass the course, the students must reach a minimal competence, indicated in the official curriculum In order to pass the course, the student must demonstrate a sufficient progress considering his own starting point Communicating assessment results must always happen in public, so every student can locate himself in the class Communicating assessment results must always be private, to avoid comparisons among students “Surprise exams” are a good motivational Purpose β Formative β SMC M SD Certifying 0.28 Anti 0.15 0.10 2.39 1.095 Certifying 0.24 Pro 0.23 0.11 4.06 1.153 Certifying 0.53 Anti 0.12 0.29 2.81 1.185 Certifying 0.07 Pro 0.45 0.21 4.23 .849 Certifying 0.53 Anti 0.22 0.33 2.54 1.231 Certifying -0.26 Pro 0.18 0.10 3.48 1.123 Certifying 0.56 Anti -0.18 0.35 3.89 .964 Certifying 0.44 Pro 0.07 0.20 3.55 1.033 Certifying 0.39 Anti 0.22 0.20 1.86 1.004 Certifying 0.03 Pro 0.19 0.04 3.55 1.214 Learning 0.32 Anti 0.21 0.14 2.15 1.103 This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie item ap02 ap03 ap04 ap05 ap06 ap07 ap08 ap09 ap10 e01 e02 e03 e04 e07 e08 Spanish motivador para los alumnos El alumno siempre debe estar informado de la intención evaluativa del profesor Es imprescindible que los alumnos se conciencien del nivel que van alcanzando según el baremo establecido Es necesario que cada alumno sea consciente de su propio avance desde su propio punto de partida Evaluar el aprendizaje no les supone a los alumnos una ocasión de aprendizaje nueva Cada ocasión de evaluación es también una ocasión de posible nuevo aprendizaje Si no hubiera evaluación del aprendizaje sería imposible motivar a los alumnos para estudiar La evaluación vista como amenaza de castigo o promesa de premio no ayuda al aprendizaje Lo mejor para el alumno tras una evaluación negativa es hacer borrón y cuenta nueva Cuando hay malos resultados de evaluación, el alumno debe reflexionar sobre sus errores La evaluación del aprendizaje y la enseñanza no se deben mezclar La evaluación del aprendizaje y la enseñanza deben ser coherentes la una con la otra La evaluación del aprendizaje supone una pérdida de tiempo y bastante estrés La evaluación del aprendizaje de los alumnos es la brújula imprescindible de la enseñanza Las actividades de evaluación deben diferenciarse claramente de las actividades de aprendizaje Cualquier actividad de aprendizaje puede ser English tool for students The student must always be informed about the assessment intention of the teacher It is indispensable that the students get aware of their learning level according to the standards It is necessary that the students get aware of their own learning improvement, considering their particular starting point Learning assessment does not imply a new learning chance. Each assessment occasion is also a new opportunity for learning If there was not learning assessment, it would be impossible to motivate students to learn Assessment understood as a threat of punishment or promise of Price does not help to learn The student’s best option after bad assessment results is to make a clean slate If there are bad assessment results, the students must reflect on their mistakes Learning assessment shouldn’t be mixed up with teaching Learning assessment and teaching must be coherent Assessment implies a loss of time and quite a stress Learning assessment is the indispensable compass of teaching Purpose β Formative β SMC M SD Learning 0.29 Pro 0.35 0.21 4.08 1.100 Learning 0.48 Anti -0.47 0.44 4.10 .938 Learning 0.04 Pro 0.61 0.37 4.64 .608 Learning 0.20 Anti 0.49 0.28 1.99 1.149 Learning -0.02 Pro 0.58 0.34 4.45 .733 Learning 0.41 Anti -0.15 0.19 3.05 1.149 Learning -0.03 Pro 0.12 0.02 3.98 1.209 Learning 0.40 Anti 0.37 0.30 1.91 .997 Learning 0.24 Pro 0.29 0.14 4.26 .937 Teaching 0.47 Anti 0.35 0.35 2.12 1.167 Teaching -0.20 Pro 0.65 0.45 4.47 .761 Teaching 0.13 Anti 0.52 0.28 1.72 .960 Teaching 0.10 Pro 0.41 0.18 3.76 1.020 Assessment activities and learning activities must be clearly differentiated Teaching 0.50 Anti 0.22 0.30 2.46 1.224 Any learning activity may be as well used for Teaching -0.17 Pro 0.68 0.11 4.08 1.015 This work is under Creative Commons license To cite this paper: Remesal, A. & Brown, G. (2012). Spanish as foreign language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: preliminary results from an internet inquiry. Paper presented at International Conference on Assessment: Linking Multiple Perspectives on Assessment / SIG-EARLI 2012, Brussels --http://www.ub.edu/grintie item e09 e10 r05 r06 r07 r08 r09 r10 Spanish también actividad de evaluación La evaluación del aprendizaje no debe afectar a otras decisiones docentes (objetivos, contenidos, recursos, métodos...) Cada vez que se evalúa el aprendizaje de los alumnos es también ocasión de revisar diversos aspectos de la enseñanza (objetivos, contenidos, recursos, métodos...) La evaluación del dominio de ELE, pero particularmente la evaluación externa mediante los exámenes oficiales, es imprescindible para tener un control Los exámenes oficiales de nivel de ELE ayudan a cada ciudadano a demostrar su propia competencia, por ejemplo ante futuros empleadores El docente es el único responsable de elaborar o seleccionar actividades de evaluación y corregirlas posteriormente para los alumnos Los alumnos son co-partícipes con el docente en todos los pasos de la evaluación, incluyendo la preparación de actividades y la corrección de resultados El currículo oficial determina los objetivos inexorables que cada docente debe cumplir Cada docente debe ajustar su planificación de curso a los alumnos de su grupo English the purpose of assessment Learning assessment must not affect other teaching decisions (objectives, contents, resources, methods…) Every time the students’ learning is assessed, it is also the time to revise different aspects of teaching (objectives, contents, resources, methods). Assessment of Spanish as Foreign Language, but particularly external assessment by means of official examinations, is indispensable to control. Purpose β Formative β SMC M SD Teaching 0.50 Anti 0.39 0.40 2.22 1.212 Teaching -0.10 Pro 0.29 0.47 4.54 .660 Accountability 0.65 Anti 0.00 0.42 2.93 1.070 Official SFL examinations help each citizen to demonstrate his own competence, for instance in front of likely employers Accountability 0.44 Pro 0.22 0.24 3.74 1.019 The teacher is the only responsible of designing or selecting assessment activities and evaluating them afterwards for the students Accountability 0.42 Anti 0.14 0.20 2.87 1.163 Students collaborate with the teacher in every step of the assessment process, including the preparation of activities and evaluating results Accountability -0.17 Pro 0.30 0.12 3.52 1.101 Accountability 0.67 Anti -0.08 0.46 3.12 1.057 Accountability -0.13 Pro 0.47 0.23 4.32 .801 The official curriculum determins the learning goals that every teacher must pursue The teacher must adjust his course plan to his group of students Note. Items in plain type reflect pro-formative tendency, while items in italics reflect anti-formative tendency; SMC=squared multiple correlate; β=standardised regression weight. ELE Teacher Conceptions of Assessment Table 3. Mean scores for each factor Factor M Aspects of teaching and learning Learning 3.46 Accountability 3.42 Certifying 3.23 Teaching 3.17 Tendency Pro-Formative 4.03 Anti-Formative 2.61 Aspect*Tendency Interaction Learning-Pro 4.28 Teaching-Pro 4.21 Accountability-Pro 3.86 Certifying-Pro 3.77 Accountability-Anti 2.97 Certifying-Anti 2.70 Learning-Anti 2.64 Teaching-Anti 2.13 se SD .02 .02 .02 .02 .39 .53 .44 .39 .012 .02 .40 .51 .02 .03 .03 .03 .04 .03 .03 .04 .51 .56 .61 .56 .81 .66 .57 .78 10