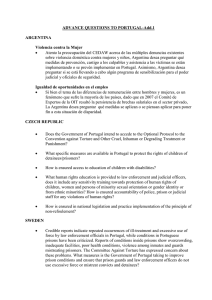

Violence against women in couples: Latin America and the

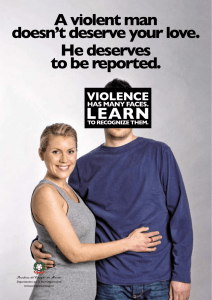

Anuncio