Organizational Culture and Multinacional Mergers: An Approach to

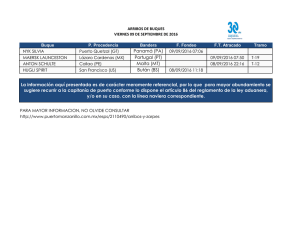

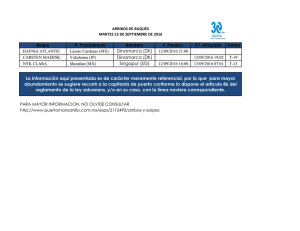

Anuncio