Time Preferences and Lifetime Outcomes

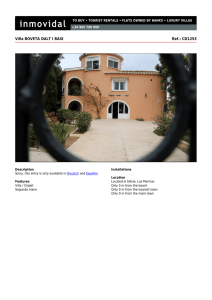

Anuncio