Los Campos de la Memoria: The Concentration Camp as a Site of

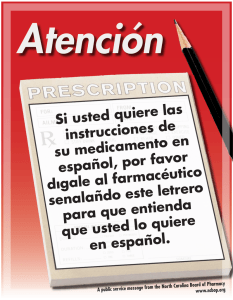

Anuncio