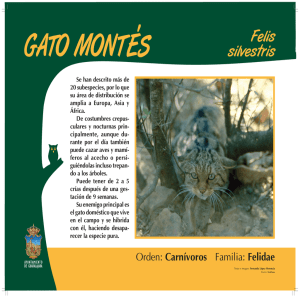

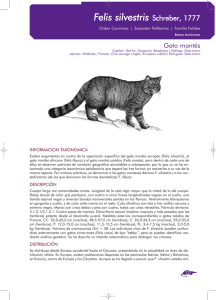

Ecología del gato montés - E-Prints Complutense

Anuncio