In format

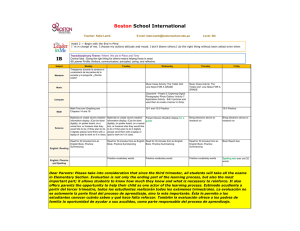

Anuncio