The Subprime Solution: How Today`s Global Financial Crisis

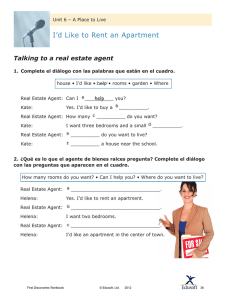

Anuncio