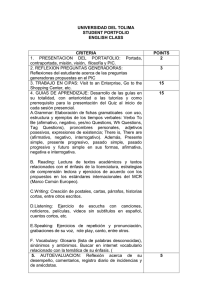

Effects of Scientific Information Format on the

Anuncio