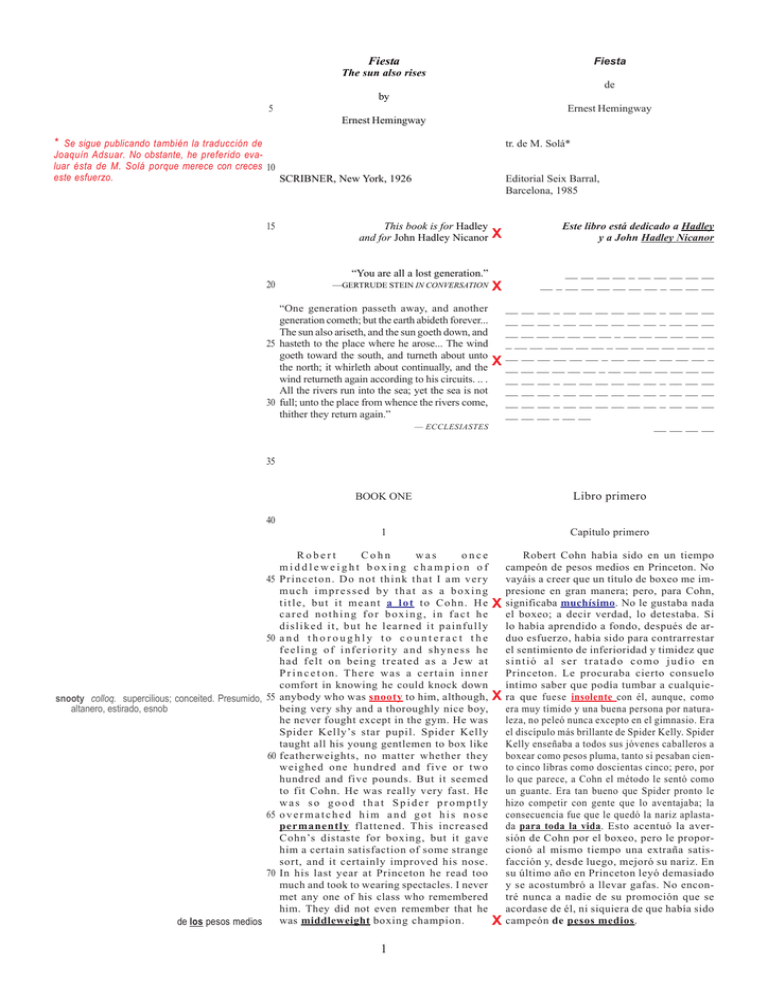

The sun also rises - rodriguezalvarez.com

Anuncio