different approaches to the difficult relationship between intelligence

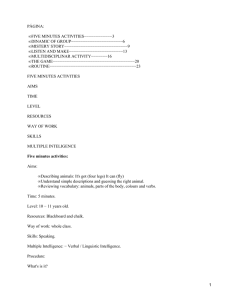

Anuncio